A Partnership Agreement outlines and describes the relationship between partnership entities (i.e. general partner and limited partners) in a joint real estate investment. It is a critical document that defines a mutual understanding of financial terms, describes the roles each party plays, decision making for the project and how actual distributions are made after deducting valid expenses. This is often the only legal document that contractually binds the General Partner or sponsor of a deal with the investors.

The Partnership Agreement sets the parameters of the expectations during acquisition, development (if any), ongoing operations, and ultimately the exit. Each of these stages represents different goals and rules for the general partner to abide by and it is difficult if not impossible to predict all scenarios at the outset . The specific terms usually include property details, investment timing, returns on capital pre-deployment, rights to additional investment, acquisition or management fees, third party fees, duty not to self-deal, calculation of IRR, and finally, in the event of a legal dispute, how that dispute will be resolved.

Note from Spencer: This is another post in a growing section we call ‘A.CRE Legal‘. One of Texas’ top real estate attorneys, Ronald Rohde, has graciously offered to share his time, expertise, and open his library of real estate legal templates for the A.CRE audience. Click here to learn more about Ron or to contact him directly.

Also, a huge thanks to Matthew Green for contributing to Ron’s video discussion on real estate partnership agreements.

To be able to even begin discussing a “template” partnership agreement, I have to state the parameters of my assumptions. Let’s assume you’re a General Partner raising funds for an acquisition of a multi-family building. This is a market rate, no tax incentive property with traditional or agency financing. You are modeling several ranges of returns and want to shift your upside as the total return to the Limited Partners increases.

On the other hand, you may be an interested Limited Partner wanting to negotiate the terms of your investment and want to learn about where and how you can extract additional protection or even asymmetric risk/returns. My clients are often family offices, small private equity shops, individual operators with a track record of developing properties in a specific niche. They want capital, but don’t need an investor who doesn’t provide the terms they want. Therefore, you should read this article understanding that while everything is negotiable, what you have to contribute to the project must be unique and not fungible. Let’s dive in and see what the legal terms actually relate to the modeling!

The General Partner can either be a legal title or a description for a Manager who has many of the same rights and responsibilities. Essentially, a general partner is the organizer who is assembling the real estate investment and is responsible for the overall success of the project. Typical duties would include placing a property under contract, coordinating the debt, signing any personal guarantees if needed, obtaining bids for renovation or construction work, calculating equity returns and compiling investor equity to execute the plan.

The Limited Partner need not be a true LP in a Limited Partnership, but can be referred to as anyone who invests passive capital and limits their own responsibility for decision making. These investors can be individuals, LLCs, equity groups, pension funds, university endowments, etc. The key factor is an investor who has more capital than time or expertise. They trade some return for the ability to passively invest.

Typically, the general partner will arrange every aspect of the investment, from hiring inspectors, drafting legal documents, and setting the total project return and profit splits. While its important to trust the general partner, every participant has an obligation to carefully review and understand the binding legal reality.

For specific closed end funds, the property should be identified with enough particularity that the seller knows which piece of land or which properties will be under contract. The alternative is a more open ended fund which will not identify with any particularity the types and assets to be invested in.

In the first scenario, calculating returns and drafting legal documents will be focused on the particular asset and project (new construction, value-add, or core). Therefore, the waterfall distributions should be easier to understand for the investment.

However, for open-ended funds, the investment may be governed by broader rules and allow for more flexibility for the general partner. The GP will have discretion to disburse without specific legal obligations written for a particular project.

While an investor agrees to invest, what does that obligation look like in reality? When does an investor have to physically transfer funds? Will the Agreement be voided if no transfer or an incomplete transfer is made?

What happens if a GP isn’t able to acquire the targeted property? Refund or look for another target? The default will allow for GP discretion and ultimate decision-making authority, but if these situations are likely, the LP may push for different terms.

Have you decided if the GP can hire affiliated vendors? How to review the agreement for clauses which prevent self-dealing or contracting with affiliated entities? Many partnership agreements explicitly permit the GP to agree to no-bid contracts, retain services or related companies, and otherwise overcharge the partnership via fees. It is critical to understand what traditional fiduciary obligations are waived via the contract. While the return structure and split may be “fair” the GP may have removed all equity risk by paying himself excessive fees at the outset.

What determines a trigger for a capital call? Typical documents allow for broad discretion of the general partner, but the language often differs about the outcome if an investor chooses not to respond to the request. Options include dilution, losing priority returns, minimal benefits, etc. You’ll se language that we start with as a default in the template document, but it can always change depending on the investor.

Often the hardest distribution is when to decide on a distribution from cash flow. If a property is increasing occupancy, but the operator is concerned about cash reserves, they may be reluctant to distribute cash just to request a cash call later. Other stages present easier (or fewer) decisions for the GP, funding everyone must pay in a lump sum for acquisition and development costs. Upon liquidation, the GP will distribute all funds. If you can estimate your motivations and concerns during this critical stage, you’ll be able to incorporate legal clauses which reflect the outcomes you need to enforce.

The two most important decisions are when to buy, when to sell, and what type of debt or financing to undertake on a property. Debt is such a powerful tool, it must be used judiciously. For example, conventional bank debt, mezzanine, government backed debt, grants, tax credits, etc. The goal is to be clea among all parties, and decide what the group goals are and then match those goals to the type of financing.

Parties and entity types are generally some combination of the following: Limited Liability Companies, Corporations, Limited Partnerships, General Partners and occasionally individuals or trust entities. For the purpose of this article, I’m going to exclude public vehicles which have an entirely different set of restrictions and concerns. A “typical” structure will have Limited Partners investing into a Limited Partnership via their own LLCs. The General Partner is an LLC who may be managed by another LLC or Corporation. The entity structure is important to understand how much transparency or corporate protection they have. Understanding authority through these vehicles will ensure that your goals are met.

I often advise clients who are less sure about a commercial real estate investment to start with a plain English summary of the investment. Then we look at models to see those descriptions reflected in a mathematical format. Finally, your lawyer should compare your understanding along with the projections to see if the legal documents continue to reflect your understanding of the terms. Legal documents cannot account for every situation, as the investment amount increases, it justifies more time (and money) spent reviewing legal documents even for a 1% risk.

We have seen a variety of methods to ensure that the mathematical model reflects the legal terms, we define IRR vs XIRR as the formula utilized in Microsoft Excel 2019. In addition, we can incorporate explicitly a model file which would reflect the parties’ intent. However, understand that if there is an error (and there certainly will be!) the court will have a hard time deciding what is fair if this approach is taken. The benefit of a purely legal document allows for intent of the parties and a neutral arbiter to decide what outcome is called for.

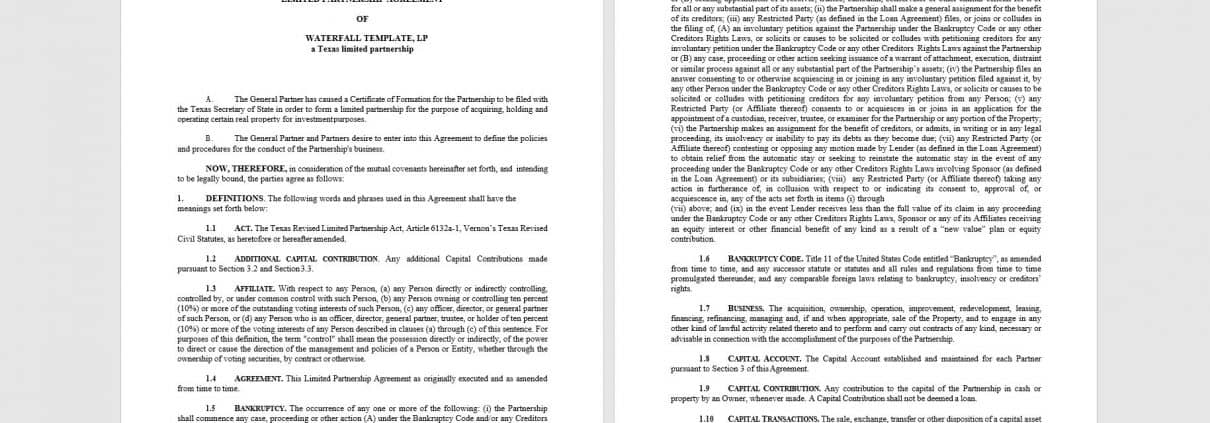

While you are encouraged to download the template to create your own document, as properties often have unique circumstances, contacting an experienced commercial real estate attorney is always encouraged to ensure it meets your specific needs.

In the following video, Ron Rohde discusses partnership agreements with seasoned real estate acquisition professional Matthew Green.

To make this legal template accessible to everyone, it is offered on a “Pay What You’re Able” basis with no minimum (enter $0 if you’d like) or maximum (your support helps keep the content coming – typical legal document templates sell for $100+). Just enter a price together with an email address to send the download link to, and then click ‘Continue’.

We regularly update the template (see version notes) . Paid contributors to the template receive a new download link via email each time the model is updated.

About the A.CRE Legal Contibutor: Ronald Rohde has over ten years of legal experience with real estate transactions, leasing, and investment. He received his undergraduate degree from Cornell University and his juris doctor from the University of Miami.